Humility Rules: Back to Benedict’s School

It was an Episcoplian priest’s sermon about humility that was the tipping point for my faith., more accurately, loss of it. Walking away from that sermon, all I could think was, “I don’t want to be humble but wise. I want wisdom!”

Only to learn, far too many years later, it’s the prerequisite. Without humility, wisdom will not find us.

I was seventeen. And believed with all my heart that I knew what I was doing. It’s astounding when we look back at our younger selves, isn’t it?

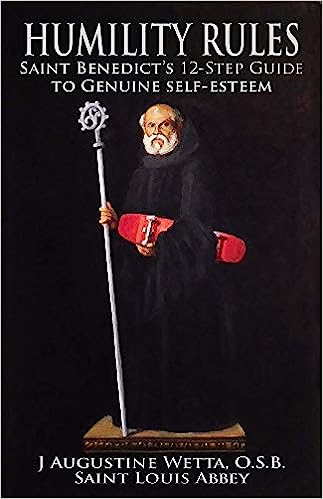

Last Wednesday, was the memorial reserved for St. Benedict. This year, my gratitude for being in the 6th century saint’s school almost flattened me. Because of that a new book jumped into my lap…you know how that happens, we’ve talked about it before. This one’s called, Humility Rules: St Benedict’s Guide to Genuine Self-Esteem by a Benedictine monk named Fr. Augustine Wetta. Humility Rules: Back to Benedict’s School.

Why so grateful for a long dead saint?

About a billion and three reasons but I’ll limit myself to three right now. Humility Rules: Back to Benedict’s School

The first and second are because the rule is written for ordinary people. St. Benedict makes it clear that he’s not writing for those of us who, like St. Thomas More, wear hair shirts under our clothes.

Or those of us whose natures are to give of ourselves, completely, freely.

No, the rule’s written for folks like me: impatient, so focused on the work before me that I miss the needs of family, hence, selfish: ordinary people.

But my newly discovered online friend has even better reasons than mine. Funnier and with great illustrations.

St. Benedict was born into a time of chaos: in the world and the church. Here’s Fr. Auustine’s engaging interpretation of Gregory the Great’s, The Life of Our Most Holy Father.

Who was St. Benedict?

“Right around the beginning of the sixth century, there lived a teenager who was bored with school. He was at the top of his class. His father was wealthy and influential. This was a smart, charismatic kid, and he seemed destined for greatness.

But he hated school. It wasn’t that he had anything against learning; he just felt like he was wasting his time.

He was training to go into politics, but the world seemed to be going down the tubes. There were gangs of kids armed to the teeth in the street; there were endless, bloody wars being fought all over the world; and there was a sudden influx of terrible diseases for which there were no cures.

There were scandals in politics and scandals in the Church. In short, the world was a mess. So he ran away. But he didn’t join the circus or find his fortune in The Big City. Instead, he went to live in a cave on the side of a mountain. There, without all the distractions of family and schoolwork and social life, he figured he could focus exclusively on holiness. He was thinking specifically of Christ’s words: “If you would be perfect, go, sell what you possess and . . . follow me” (Mt 19:21). He wanted to take those words literally.

Saint Benedict spent the next three years just praying. Ironically, all this praying made him famous. People started to come to him for advice. The next thing he knew, there were hundreds of guys living in the same mountains, trying to do the same thing. Folks even invented a name for them: the monakhoi—the “lonely men”—or, in modern English, “monks”. But each monk seemed to have his own way of doing things, with the result that there was a whole lot of chaos and not a lot of prayer going on.

So a bunch of them got together and came to Benedict as a group. “Teach us how to be real monks,” they said. So Saint Benedict wrote a handbook. It was chock full of great advice, from who should apologize after an argument, to how many times a day you should pray, to what you ought to do with old underwear, and whether you should sleep while wearing a knife.

It was so useful, in fact, that within a hundred years, virtually every monastery in Europe adopted it. We know it today as The Rule of Saint Benedict, and it is used by monasteries all over the world…”

Why humility?

It’s such a simple yet perplexing word: humility.

Father Augustine explains what it isn’t:

“At Oxford, I had a friend who lived in a castle, who invited me to stay with his family for a few days during one of our breaks. As we pulled up his driveway, and I saw this enormous piece of architecture that he calls “home”—complete with its own pond, tennis courts, golf course, and chapel—I looked over at his mom and said, “Seriously? That’s your home?” His mom looked at the castle and then at me and then back at the castle again and said, “Yes, it’s wonderful, isn’t it? We really are blessed.” I might have expected her to say something like “Well, it needs work” or “Thanks, but it’s really hard to keep up.” Instead, she looked at her castle and thanked God for it. That is true humility.”

Magnificat’s Benedict XVl Servant of Love is replete with the former Pope’s incisive, magnificent theology. I keep returning to a short piece on Joseph’s Ratzinger’s on the Chosen One for the Non-Chosen.

“Jesus, the only just man, is chosen by God to bring into the blessing those who could not benefit from it because of their sin—which is to say, all of us. Thus the chosen one is for us…for Christ, election consists in carrying the mystery of evil, which weighs upon those who, because of their fault, merit rejection…for Jesus Christ, the only one worthy of salvation, now takes its complete opposite, the whole of damnation on himself in a sacred exchange.”

Is there any other response than the realization of our nothingness? God is all, we are nothing. Yet when filled with Christ, we’re grafted on to divinity.

St. Benedict begins Chaper 7 On Humility with the scripture’s call: Whoever exalts himself shall be humbled, and whoever humbles himself shall be exalted (Luke 14:11; 18:14). 2 In saying this, therefore, it shows us that every exaltation is a kind of pride,

We know where do we look for the quintessence of humility.

In Luisa Piccarreta’s Book of Heaven, the Blessed Mother tells Luisa that no one alive can imagine the crucible of following the Divine Will each second of her life. The anguish of restraining herself from helping another because it was not the will of the Father.

STEP SEVEN

SELF-ABASEMENT Believe in your heart that you are an unworthy servant of God, humbling yourself and saying with the Prophet: “I am a worm, and no man; scorned by men, and despised by the people” (Ps 22:6). Every human being is infinitely loved and infinitely precious. We haven’t earned that divine dignity; it is a gift. Nonetheless, we convince ourselves that we must somehow show ourselves worthy of God’s love—that if we are charming or charitable or brave enough, He will feel obliged to reward us. Self-abasement is the antidote to this delusion. It is the practice of reminding ourselves that we are nothing without God’s grace and will never earn it. Ironically, this healthy sense of nothingness, understood correctly, brings with it a deeper sense of confidence and freedom.

As a last thought from our Benedictine friend, there’s this:

But God wants you and me to be saints—to live lives of heroic virtue—to give and give and give until it hurts!” …

My point is that humility should never be confused with mediocrity. Perfect holiness is the purpose for which we were created, so we can’t allow ourselves to be comfortable with the status quo. The minimum is not enough.

Does this scare you?

t should. “Everyone to whom much is given, of him much will be required” (Lk 12:48). But it should also thrill you, because it means you are infinitely important and always loved. What’s more, you have a whole army of saints at your back.